By JEAN LUC NEPTUNE

I recently received the good news that I passed the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) recertification exam. As background, ABIM is a national physician evaluation organization that certifies physicians who practice internal medicine and its subspecialties (all other specialties have their own certifying body such as ABOG for obstetricians and gynecologists and ABS for surgeons). Physicians practicing in most clinical settings must be board certified to be credentialed and eligible to work. Board certification can be achieved by taking an exam every 10 years or by participating in a continuing education process known as LKA (Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment). I decided to take the big 10 year test instead of following the LKA approach. For my ABIM-certified physician colleagues wondering why I did the 10-year program versus the LKA, I’m happy to have a side discussion, but it was largely a matter of career timing.

Of note, board certification is different from the USMLE (United States Medical Licensing Examination), which is the first in a series of licensure hurdles that doctors face in medical school and residency, and involves 3 separate tests (USMLE Step 1, 2, and 3). After completing the USMLE steps, acquiring a medical license is a separate state-mediated process (I am active in New York and inactive in Pennsylvania) and has its own set of requirements that one must meet in order to practice in any state. If you want to be able to prescribe controlled substances (opioids, benzos, stimulants, etc.), you will need a separate license from the DEA (the Drug Enforcement Administration, which is a federal entity). Simply put, you need to complete a lot of training, score high on many standardized tests, and acquire a ton of certifications (which cost a lot of money, by the way) to be able to practice medicine in the United States.

What I learned when preparing for the ABIM recertification exam:

1.) There is A LOT TO KNOW about being a doctor!

To prepare for the exam I used the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) review course, which included approximately 2,000 in-depth case studies covering all subspecialty areas of internal medicine. If each case is estimated to involve mastery of dozens of medical knowledge, the exam requires a doctor to remember tens of thousands of different pieces of information just for one specialty (remember that medical vocabulary alone consists of tens of thousands of words). Furthermore, individual facts mean nothing without a mastery of the basic underlying concepts, models and frameworks of biology, biochemistry, human anatomy, physiology, pathophysiology, public health, etc., etc. Then there’s everything you need to know for your specific specialty: medications, diagnostic frameworks, treatment guidelines, etc. It’s a lot. There’s a reason it takes almost a decade to gain any competency as a doctor. So whenever I hear a non-doctor say they’ve been reading about XYZ and “I think I know almost as much as my doctor!”, my response is always “No, you don’t. Not at all. Not even a little bit. Stop it.”

2.) There are so many things we DON’T KNOW as doctors!

What particularly caught my attention when doing my review was how often I came across a case or presentation where:

- It is not clear what causes a disease,

- The natural history of the disease is unclear.

- We don’t know how to treat the disease,

- We know how to treat the disease but we don’t know how the treatment works.

- We do not know which treatment is more effective or

- We don’t know which diagnostic test is best.

- And it goes, and it goes, and it goes…

It is estimated that there are more than 50,000 (!!) active journals in the field of biomedical sciences. publishing more than 3 million (!!!!) articles per year. Despite all this generation of knowledge, there is still a lot we don’t know about the human body and how it works. I think some people find doctors arrogant, but anyone who really knows doctors and medical culture can tell you that doctors possess a deep sense of humility that comes from knowing that very little is actually known.

3.) Someday soon, the computer doctor will SURELY be smarter than the human doctor.

The entire time I was preparing for the exam, I told myself that there was nothing I was doing that a sufficiently advanced computer couldn’t accomplish.

If we abstract from what most doctors do (diagnose a disease and prescribe a treatment), it is pretty clear at this point in the history of the development of artificial intelligence that a computer will be able to do MOST of what a doctor does very soon.

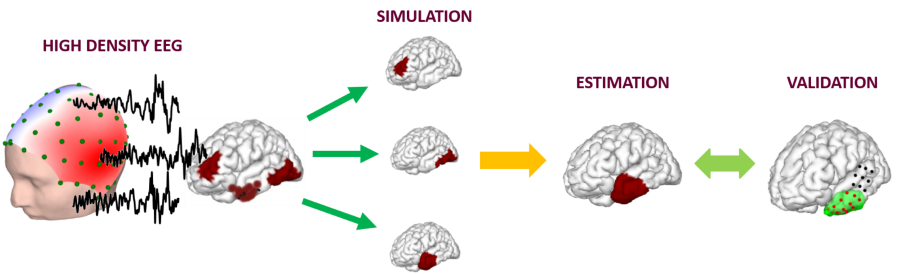

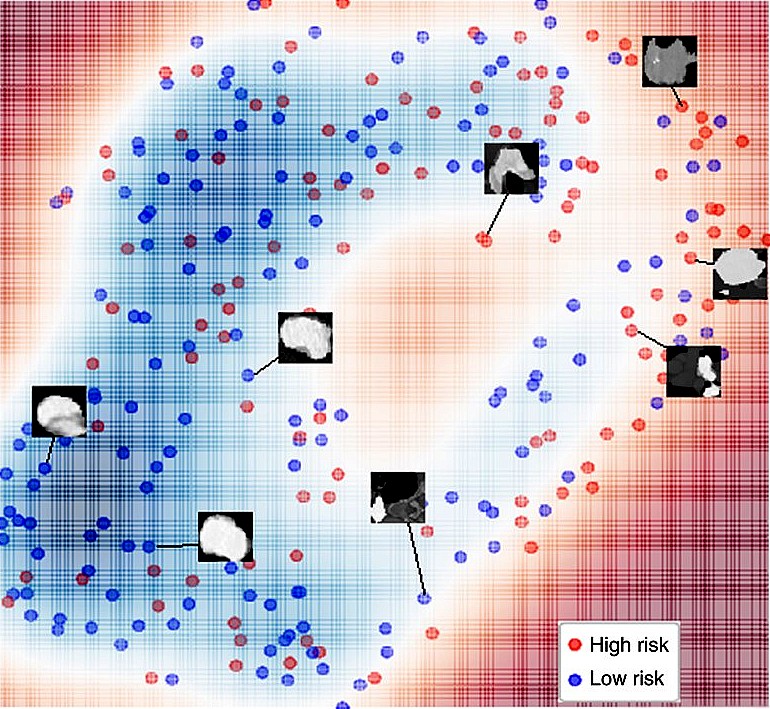

Conceptually, making a diagnosis is fairly simple: gathering information about a patient’s presentation and evaluating complex patterns involving the patient’s history, signs, symptoms, and various tests. While human doctors are capable of recognizing hundreds and thousands of patterns, there are human limits to our abilities that are driven by our finite memory, our prior experiences, and our access to information. However, existing AI systems have access to virtually unlimited information and more powerful pattern recognition algorithms and will soon be able to identify disease patterns better than even the best doctor.

Prescribing treatment is also quite simple: based on the characteristics of this patient, the disease, the nature/stage of the disease, the patient’s preferences, etc., recommend what the literature (clinical guidelines, peer-reviewed journal studies, etc.) shows is the most effective treatment and will produce the least harm. As humans, there are a limited amount of magazine articles we can read and a limited amount of information we can store in our brains. AI systems can access the accumulated knowledge of all of humanity and will soon be able to review ALL literature in an instant to guide treatment decisions.

Recently published research already shows that AI systems can match or surpass the performance of human doctors. Many people will object and say that machines don’t really reason, which is true for the moment, but the technology to reason is probably not that far away. Since these technologies are improving at an exponential rate, it is quite clear that an unequivocally better machine will eclipse the cognitive performance of human doctors in a very short period of time: AT MAXIMUM, 10 years. I am convinced that the day will soon come when patients will ask their doctor “what does the AI system recommend?”

4.) What the computer can’t do yet is BE HUMAN (at least not yet).

In studies that show a computer working alongside a doctor, what is often overlooked is that the computer is working off a well-summarized case presentation (like the ones you used to study for boards) with all the relevant data. What these studies overlook is that one of the most important functions of the doctor is to interact with another human being to access the information necessary to reach a diagnosis and recommend treatment. It is rare that as doctors we are given a good summary with all the pertinent information. Often the other human being is emotionally disturbed, or under the influence of a substance, or lying, or unconscious. Much of what we can do as human doctors is put together a story using our human senses (sight, smell, touch, hearing, thankfully not taste) to inform our judgment. A large part of medical training is learning about human psychology, human culture, and human history that we then use to inform the science we have mastered.

Another important aspect of being a human physician is our role as counselors, advocates, and managers of the care of individual patients and broader patient populations. After all, patients need someone to help them understand a serious diagnosis or to support them when making difficult decisions about treatment options. The modern medical system has evolved into a more transactional model in which doctors and patients are often deprived of deeper human interactions, but new technologies present the opportunity to perhaps reduce the administrative burden on doctors and patients so that more time can be devoted to person-to-person therapeutic interactions.

Someday we will have machines technologically advanced enough to fully emulate humans (it is interesting to note that the original Nexus-6 “replicants” from the Blade Runner Tyrell Corporation exist in the fictional year 2019), but for now nothing makes humans better than a human.

5.) Technology can help us become better doctors right now.

What many people don’t know is that the daily job of being a doctor sucks. For every hour of direct clinical care provided The average doctor spends another 2 hours performing administrative tasks. Most doctors did not sign up to spend their working careers entering data into horribly designed EMRs, waiting for insurance prior authorization, or asking patients the same information over and over again. I am excited that my role at Commure gives me the opportunity to contribute to technology that improves the lives of doctors and patients.

Ambient writing is a transformative technology that is helping physicians reduce the administrative burden of documenting care by up to 80%, reducing physician burnout and allowing them to reclaim the joy of being a physician. Co-Pilot technologies are putting all the medical research ever published at the fingertips of doctors in a way that reminds me of how access to the Internet (and sources like UpToDate) changed the way we provide healthcare 25 years ago. Finally, Agentic AI is helping to reduce the “scut” work of being a doctor by automating and routineizing repetitive tasks that do not deserve human attention.

I know that the introduction of new technologies makes many people fear for the future of employment, which is a reasonable concern in these uncertain times. That said, there is so much attention we are NOT providing because we simply don’t have the resources, and I think the story of the next few years will be using technology to catch up on what we should have been doing in the first place. I encourage my physician brothers and sisters to resist fighting technology and instead work to make technology fit our needs. The development of modern EMR came at the physician’s expense to improve the lives of other stakeholders who are not at the bedside. We can’t let that happen this time.

(AI Certification: I attest that this essay was written WITHOUT the use of any artificial intelligence assistance, but with some editing by my very human wife.)

JL Neptune is a New York-based internal medicine physician and executive medical director of Commure.