Along with fibers made from wood, the fungus produced a coating that blocks the absorption of water, oil and grease, the team reported in the journal of the American Chemical Society (ACS). Langmuir.

US researchers have developed a way to waterproof materials using edible mushrooms that has the potential to replace single-use plastic products and paper cup liners. Along with fibers made from wood, the fungus produced a coating that blocks the absorption of water, oil and grease, the team reported in the ACS journal Langmuir. At least three days of fungal growth were needed for an effective water barrier to develop.

In a proof-of-concept study, the waterproof film was grown on common materials such as paper, denim, polyester felt and thin wood, revealing its potential to replace plastic coatings with natural and sustainable materials.

“Our hope is that by providing more ways to potentially reduce our reliance on single-use plastics, we can help decrease waste ending up in landfills and the ocean – nature offers elegant and sustainable solutions to help us get there,” he said. Caitlin Howell, corresponding author of the study from the University of Mainein a statement from ACS.

Mushrooms are more than their hats; Underground they form an extensive interwoven network of feathery filaments called mycelium.

Recently, researchers have been inventing water-resistant materials made from these fibrous networks, including gauze and leather-like electrically conductive threads, because the surface of the mycelium naturally repels water.

Additionally, films made from spongy wood fibers used in papermaking (specifically, a microscopic form called cellulose nanofibrils) can create barriers to oxygen, oil, and grease.

Howell and his colleagues wanted to see if the edible turkey tail mushroom (Trametes versicolor) would grow with cellulose fibrils forming a protective layer on various materials. Their goal was to develop a natural, food-safe film with water, oil and grease resistant properties.

To create the movie, the researchers first combined T. versicolor mycelium with a nutrient-rich solution of cellulose nanofibrils. They applied thin layers of the mixture onto denim, polyester felt, birch veneer and two types of paper, letting the fungus grow in a warm environment.

Placing the samples in an oven for a day inactivated the fungus and allowed the coating to dry. At least three days of fungal growth were needed for an effective water barrier to develop.

And after four days, the new coat didn’t add much thickness to the materials (about the same as a coat of paint), but it did change their colors, forming mottled patterns of yellow, orange or tan.

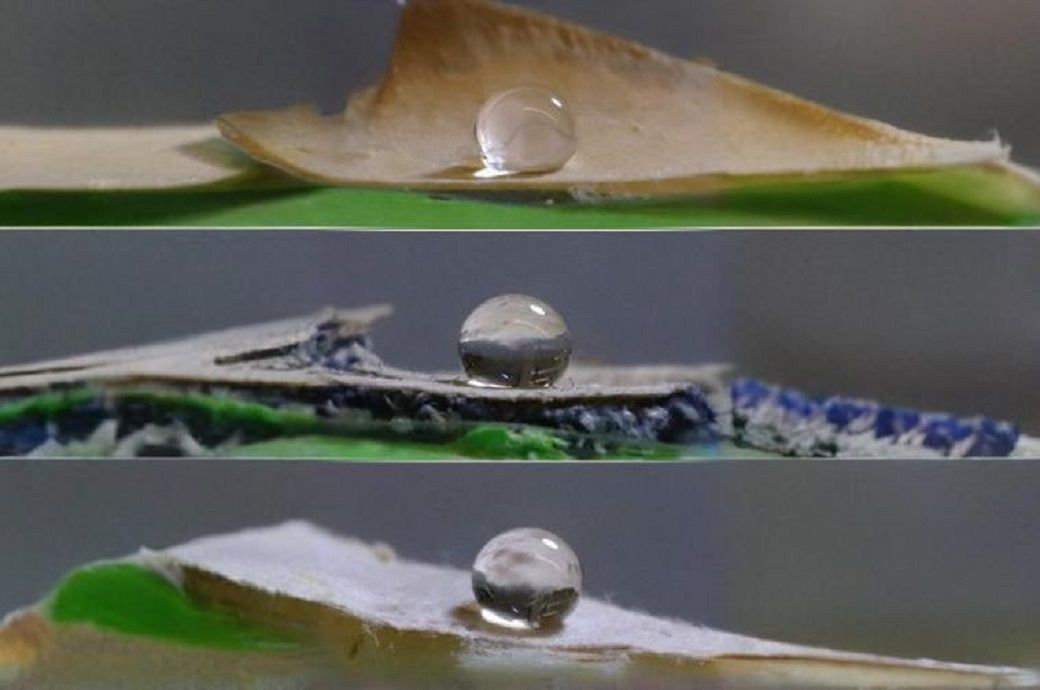

Water droplets placed on fungal-treated textiles and paper formed bead-like spheres, while similar droplets on untreated materials flattened or soaked completely.

Additionally, the fungal coating prevented the absorption of other liquids, including n-heptane, toluene, and castor oil, suggesting that it could be a barrier to many liquids.

The researchers say this work is a successful demonstration of a food-safe fungal coating and shows the potential of this technology to replace single-use plastic products.

Fiber2Fashion News Desk (DS)