It was a quiet winter afternoon in the English seaside town of Cley, population 400. 2014 had barely passed a week and everyone was beginning to return to post-Christmas life. Peaceful. Don’t worry. Until a flock of geese shot down a US Air Force helicopter in his backyard.

The helicopter was part of a formation of two aircraft on a training mission, two Sikorsky HH-60G helicopters, better known as Pave Hawks. It was a workhorse of the US Air Force, in use since 1982 and used in almost all military operations in the intervening years. While the Pave Hawk is now being phased out in favor of the Jolly Green II, only the US Air Force still operates 99 Pave Hawks.

A key reason for this is that the Pave Hawk is designed to reach places other aircraft cannot. It flies low, below radar coverage, hugging the terrain in what the military knows as earth nap flight. The forward-facing infrared system makes them especially suitable for nighttime low-level personnel recovery operations.

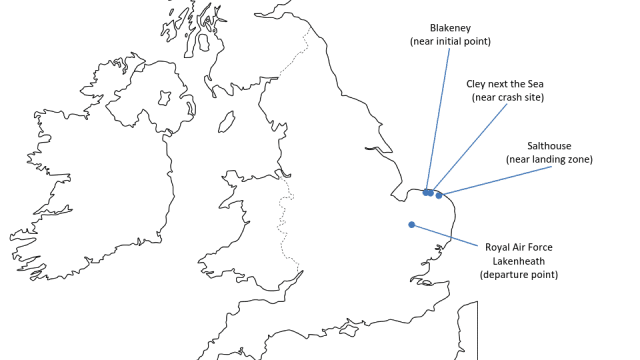

This particular Pave Hawk, tail number 88-26109, was assigned to the 56th Rescue Squadron, operating out of RAF Lakenheath as part of the 48th Fighter Wing of United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE). The mission that night, January 7, 2014, was for the two Pave Hawks to fly in formation for a training scenario rescuing a downed F-16 pilot in the dark.

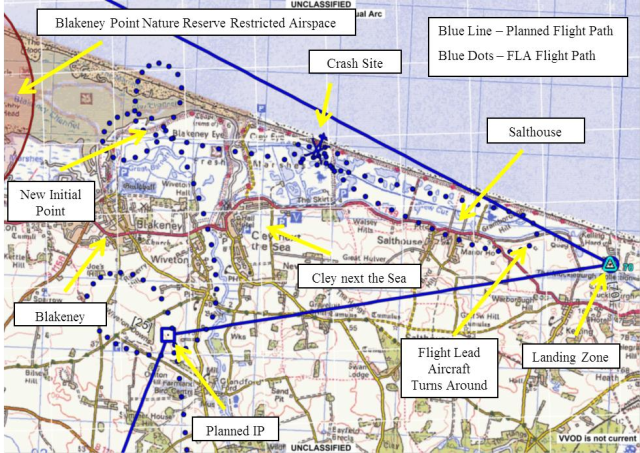

The pilot of the crashed helicopter and the co-pilot of the main helicopter developed the mission plan the day before. All crew members would wear night vision goggles. They would depart RAF Lakenheath an hour after sunset and fly about 36 nautical miles to a point south of Blakeney. There they would orbit, verify the status of the hypothetical downed pilot, and conduct a threat assessment. The two helicopters would remain in formation and fly at low level for approximately three and a half nautical miles to a landing zone near the village of Salthouse, a site frequently used for training missions. At such low altitudes and in the dark, their options were limited. The planned route had to avoid obstacles, air traffic and local noise-restricted areas.

The mission plan met all operational requirements and was authorized.

That same day, the day before the accident, the Wildlife Trust counted a flock of around 400 geese along with other birds roosting in the area.

Blakeney Point Nature Reserve is a well-known habitat for large flocks of migratory birds and is designated as an avoidance zone: “avoid 500 feet or 2 nautical miles for flight options.” The UK Military Low Flying Manual recommends that aircrew cross coastlines at right angles and above 500 feet above ground level to avoid bird strikes. However, this mission was a low-level night tactical formation, intended for flying under cover of darkness and required flying below 500 feet.

A month earlier, in December 2013, a storm surge had flooded coastal mudflats, including Blakeney Reserve. Several flocks of birds had moved southeast to rest in drier terrain.

The crew had access to bird activity maps during planning. The December map showed moderate bird activity west of the landing zone at dusk. The January map, published on the day of the training mission, indicated an area of low level bird activity over Cley Marshes. The crew had access to the maps for reference during mission planning. The maps indicated an area of moderate evening bird activity (defined as one hour before and after sunset) west of the proposed landing zone. As the mission departed after sunset and would arrive at the landing zone an hour after nightfall ended, this risk was considered mitigated.

The key point: All required procedures were followed to evaluate risks and benefits.

On the day of the accident, the Wildlife Trust did not count any geese.

The two-plane formation took off at 17:33: 90 minutes after sunset and half an hour after the end of dusk, half an hour after the moderate dusk bird danger warning expired. The helicopters flew north to begin their simulated mission to rescue the hypothetical downed F-16 pilot under the cover of darkness.

On the way to the first point, they carried out simulated countermeasures against threats. The helicopters arrived at the first point after 25 minutes of flight and began an orbit to the left, simulating a check on the status of the downed pilot.

Strong winds near the initial holding point, south of Blakeney, caused the formation to move northwards towards Blakeney Point Nature Reserve. Blakeney Reserve is a designated no-fly area and they were approaching areas marked with moderate and severe dangers to birds. The training profile meant they flew low, just 110 feet above ground level, which meant they risked causing noise nuisance if they got too close to populated areas.

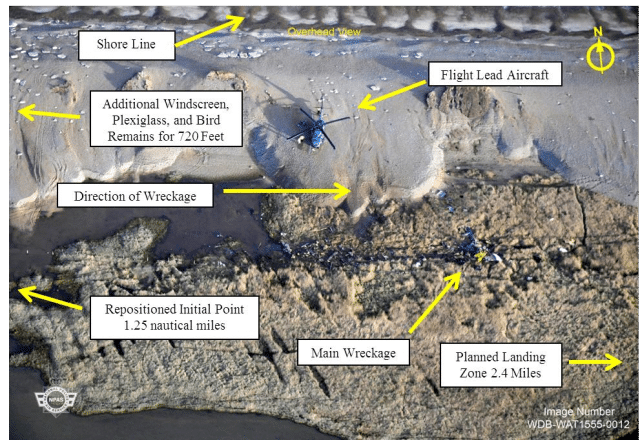

The helicopter’s lead pilot moved the orbit 1.3 miles to the north, establishing a new “home point” closer to the coast. This kept them away from Blakeney Reserve and the known danger zone for birds. The new route kept them in an area marked with a “low” bird danger rating, but also passed through Cley Marsh, part of a protected wildlife area.

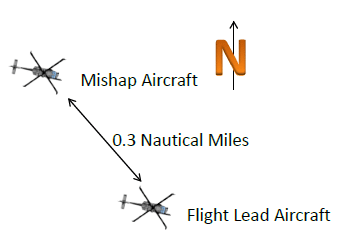

They reached the new starting point and completed two full orbits to the left. They then exited orbit to fly east at 100 feet above ground level at 110 knots indicated airspeed. The two helicopters maintained a separation of 0.3 nautical miles, with the accident helicopter positioned behind and to the left of the leader.

As they approached Cley Marsh, a flock of geese rose into the air, probably frightened by the noise of the engines. Within a minute, the birds had risen to a height of 110 feet.

The Pave Hawk in flight lead position, still about 0.3 miles ahead, didn’t see the geese at all. But behind them, the ascending geese collided with the other helicopter. That type of goose weighs between 6 and 12 pounds. At least three crashed through the windshield and entered the cockpit, leaving the pilot and co-pilot unconscious.

At least one goose hit the gunner in the open door, knocking him unconscious. Another goose crashed into the nose of the helicopter, disabling the flight path compensation and stabilization systems. The flight path stabilization system dampens changes in pitch, roll and yaw to keep the aircraft stable in flight. Both components are part of autopilot. With the autopilot disabled, the stick fell to the left.

At the time, the Pave Hawk was in a tremendously dangerous state: just 110 feet off the ground with the autopilot disabled and both pilots unconscious. It began to bank to the left until it reached a critical point and lost all vertical lift.

The only crew member still conscious was the flight engineer, who probably didn’t even realize what was happening. The report grimly notes that it takes a human being 3.4 seconds to perceive and process sensory information.

Three seconds passed from the bird strike to the crash.

The Pave Hawk was destroyed on impact, killing all four crew members.

The entire crew wore full helmets designed to withstand a force of 150G. All helmets were cracked by the force of the impact. Feathers were found inside and outside the helmets.

The report notes that a slightly below-average goose, weighing about 7.5 pounds, would impact, as an oddly specific point of comparison, 53 times the kinetic energy of a baseball moving at 100 miles per hour. The geese exceeded the design tolerance of both the windshield and helmets, applying more than 300 G of force upon impact.

He United States Air Force Aircraft Accident Investigation Board He ultimately concluded that the accident was caused by multiple bird strikes, but offered no contributing factors that could have mitigated the risk. They found no evidence that mission planning or planning oversight contributed to the mishap.

The crew were briefed on bird activity in the areas, with updated reports of bird activity in the area. These referred to increased bird activity at dusk, but as they operated after dark there was no reason to consider this a concern. The night vision goggles restricted the crews’ field of vision, which could have prevented them from seeing the geese take flight. But then, it’s impossible to say that the geese would have been visible to the naked eye in the dark, much less whether there was time to do anything about it.

It’s a brutal demonstration of how lethal a bird strike can be, destroying four lives and a $40 million plane in seconds. Ultimately, the Air Force can only hope it doesn’t happen again.