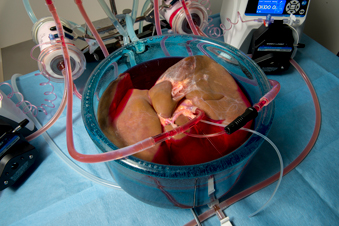

Scientists have significantly expanded the amount of time human livers can be stored for transplants by modifying a previous protocol to extend the viability of rat livers. Previously, human livers were only viable for an average of nine hours, but the new preservation method maintains liver tissue for up to 27 hours, giving doctors and transplant patients a much longer period of time to work with.

The research is supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), both part of the National Institutes of Health.

Like a glass container broken by frozen water, when cells freeze, they often suffer irreparable damage. Since human cells are especially sensitive, donor livers are stored above freezing at 4 degrees Celsius. As a result, doctors can typically only preserve human livers for nine hours before the chances of a successful transplant decrease dramatically. This short period of time makes it more difficult, and sometimes impossible, to get organs to compatible patients further away.

“Delivering viable organs to compatible recipients within the window of viability can often be the most challenging aspect of organ transplantation,” said Seila Selimovic, Ph.D., director of NIBIB’s Engineered Tissues program. “By giving doctors and patients more time, this research could one day affect thousands of patients waiting for a liver transplant.”

However, while the techniques worked with rat livers in those earlier studies, they were unsuccessful when applied to human livers, which are 200 times larger. The size difference significantly increased the risk that ice crystals would begin to form spontaneously (heterogeneous ice nucleation), which would make the organ unusable for transplant. In a paper published in Nature Biotechnology on September 9, Reinier de Vries, MD, a surgical researcher, Shannon Tessier, Ph.D., an instructor in surgery at MGH and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Uygun, and his collaborators at MGH detail three new protocol steps to prevent ice nucleation and preserve human livers for up to 27 hours.

“With supercooling, as the volume increases, it becomes exponentially more difficult to prevent ice formation at subzero temperatures,” de Vries said. “Before, there were a lot of experts saying, ‘well, this is amazing in small rats, but it won’t work in human organs,’ and now we’ve managed to scale it up 200-fold from rat livers to humans using a combination of technologies.”

The first step was to limit the contact of the stored liquid with air. When supercooled, the livers are immersed in the protective supercooling solution. The researchers found that the risk of ice crystals forming increased significantly in areas where the solution was in contact with air. To eliminate this risk, the scientists removed air from the storage solution bag before supercooling, effectively eliminating the possibility of spontaneous ice nucleation on the surface of the organ.

Next, the researchers included two additional ingredients in the protective solution to help protect the hepatocytes. The first additive, trehalose, helps protect the cell and stabilize cell membranes. The second, glycerol, supports the protective properties of the added 3-OMG glucose compound in the above experiments. Both additives have been used in the cryogenic preservation of cells in the laboratory but had not been used in the preservation of organs for transplants.

Finally, they developed a new method of delivering the preservation solution to the liver. The traditional method of administering the preservative solution used in previous studies is to manually flow the preservative solution through the tissue. However, the new protective solution is thicker than traditional solutions and can damage the cells that line the inside of blood vessels. Additionally, the higher viscosity means that the solution is often not distributed evenly throughout the organ, increasing the chance that ice nucleation will spread and freeze the liver. To combat this problem, the researchers used mechanical perfusion (a way of delivering oxygen and nutrients to the capillaries of biological tissues while they are outside the body) at 4 degrees Celsius with traditional protective solution. They then slowly lowered the temperature while increasing the concentration of the new protective additives. The stepwise approach allowed the liver tissue to adapt and the solution was able to spread throughout the organ more evenly.

While researchers have yet to implant a preserved liver using this new method in a human subject, traditional standards for assessing liver viability indicate that this process will not negatively affect the organ.

“This new method of liver preservation exemplifies NIH’s goal of fostering the discovery and translation of innovative ideas,” said Averell H. Sherker, MD, director of the NIDDK program for liver diseases. “With more research, organs will be able to travel greater distances and benefit the most critically ill patients who require a liver transplant.”

This work was supported by the NIH National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases under award numbers R21EB023031, R01DK096075, R01DK107875, R01DK114506.

###

NIBIB’s mission is to improve health by leading the development and accelerating the application of biomedical technologies. The Institute is committed to integrating the physical and engineering sciences with the biological sciences to advance basic research and healthcare. NIBIB supports research and development of emerging technologies within its internal laboratories and through grants, collaborations and training. More information is available on the NIBIB website: http://www.nibib.nih.gov.

NIDDK, a component of the NIH, conducts and supports research on diabetes and other endocrine and metabolic diseases; digestive diseases, nutrition and obesity; and kidney, urological and hematological diseases. Spanning the entire spectrum of medicine and affecting people of all ages and ethnic groups, these diseases encompass some of the most common, serious and disabling conditions affecting Americans. For more information about the NIDDK and its programs, see http://www.niddk.nih.gov.

The National Institutes of Health, the nation’s medical research agency, includes 27 institutes and centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The NIH is the primary federal agency that conducts and supports basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures of common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov.