A long-standing aspiration of researchers and doctors has been the ability to repair DNA in a living cell or organism, especially in human patients with disease-causing genetic mutations. Now, scientists with partial financial support from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University are closer than ever to achieving this goal. Researchers have designed a more precise and versatile genome editing system, called core editing, that harnesses the power of CRISPR-Cas9 in combination with another protein, reverse transcriptase, to directly edit DNA in human cells.

“We have reached a new milestone in curing genetic diseases in adults with this remarkable improvement of the powerful CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing system,” says David Rampulla, Ph.D., director of the NIBIB program in Synthetic Biology for Technology Development. “This was an ambitious project and I am eager to see how scientists will use the new tool in basic research and in the clinic.” The study published in Nature by David Liu, Ph.D., the Richard Merkin Professor at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and his team led by postdoctoral fellow Andrew Anzalone, Ph.D., reported 175 successful DNA edits using their master edit. The pair believe that primary editing has the potential to correct about 89% of known disease-causing mutations in DNA.

In the classical CRISPR-Cas9 system, a guide RNA guides the Cas9 enzyme to a specific DNA site where it cleaves both DNA strands. After the cut, the cell recognizes that the DNA has been damaged and will initiate one of several repair mechanisms. Scientists hijack the repair process and can introduce changes at specific sites in the cell’s genome. However, the original CRISPR-Cas9 system is often inefficient at properly replacing DNA bases and produces a mixture of correct and incorrect edited DNA products.

Of the three billion DNA bases in the human genome, devastating diseases can occur when just one letter of a cell’s DNA is incorrect. It is challenging to change just one DNA letter to a different letter using classic CRISPR-Cas9, but the primary editing technique can allow this change much more easily.

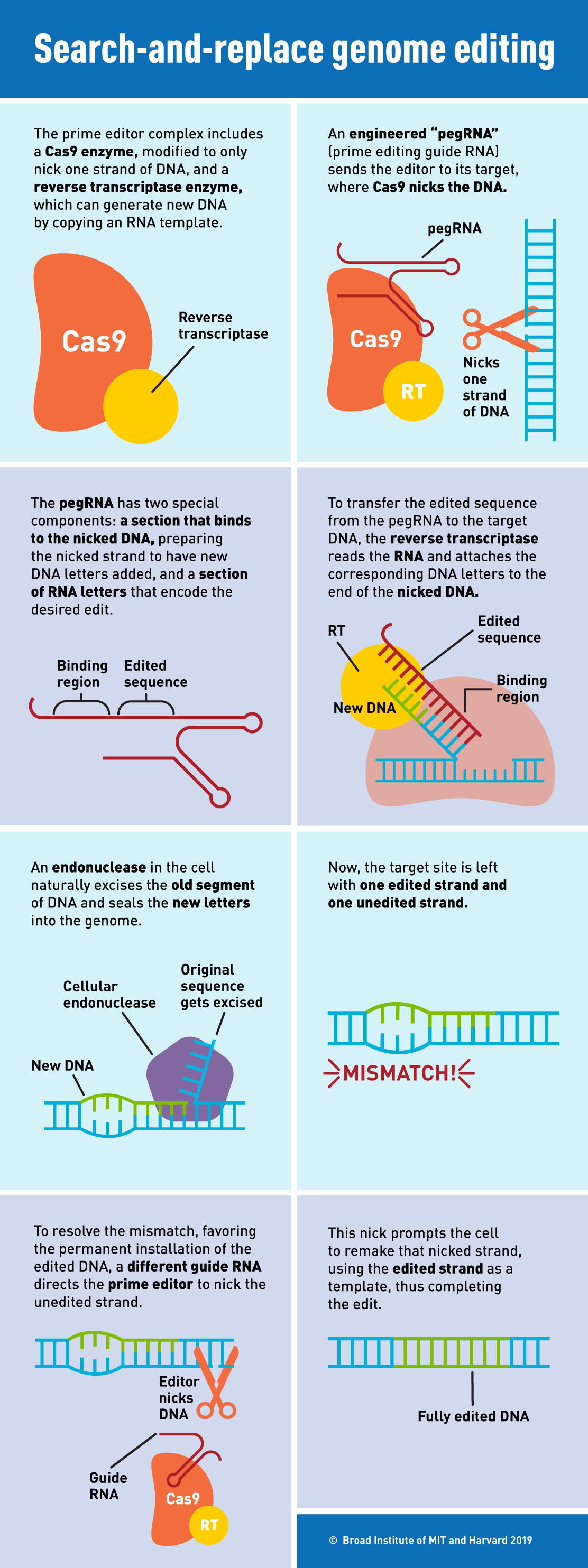

“If CRISPR-Cas9 and other programmable nucleases are like scissors that remove strands of unwanted DNA bases, a master editor can be compared to a word processor, where one or more unwanted DNA bases are searched in the genome and then replaced,” described lead researcher Liu. The core edit is made up of two components: an engineered protein and an engineered RNA. A deactivated Cas9 protein fused to an engineered reverse transcriptase enzyme forms the core editing protein that is vital to this new technique.

The designed guide RNA, called prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA), contains two key sequences: one that targets a specific DNA site in the cell’s genome and another that includes the desired edits in the cell’s genome. The pegRNA directs Cas9 to the target site of the DNA, where it cuts only one strand of DNA instead of cutting both strands. Reverse transcriptase then reads the

remaining pegRNA sequence and adds the edited DNA sequence to the nicked target DNA strand, letter by letter, copying the corresponding part of the pegRNA. Finally, the master editor guides the cell to use this new DNA sequence to replace the original unedited DNA sequence in both DNA strands.

“Andrew Anzalone led this project and conceived the initial idea of incorporating DNA edits directly into the guide RNA,” Liu said. From there, the team had to find the best way to transcribe the information efficiently and accurately into the DNA sequence. The researchers began experiments in simpler yeast systems, but a big hurdle they had to overcome was achieving the edits in real human cells. “I never thought I’d be excited by results showing an editing success rate of only 3% in human cells, but that’s when I knew our system would work after a little optimization.” So far, the team reports efficiency rates of between 20% and 50% after initial optimization.

In addition to improving the efficiency of human cells, the team is in the process of characterizing possible ways in which master editors may affect human cells. Additionally, the editing system was primarily tested using a widely used human cancer cell line, but the researchers still need to test the compatibility of the master editor with other human cell types. Finally, to explore the potential for using the technology in human therapeutics, it is first necessary to optimize administration methods to work with live animals.

Harnessing the power of CRISPR-Cas9 techniques with novel approaches like this new editing tool will continue to push the boundaries of genetic research. “Each type of genome editing technology has its strengths and weaknesses and will play a role in basic research and human therapeutic applications,” Liu said. “Primary editing is very versatile and produces fewer unwanted gene products than other genome editing systems, making it valuable to the scientific community.”

Funding for this study was provided in part by the National Institutes of Health, including NIAID, NHGRI, NIBIB, and NIGMS (U01AI142756, RM1HG009490, R01EB022376, R35GM118062, T32GM007726), the Merkin Institute for Transformative Technologies in Healthcare, and several grants.

Anzalone AV, et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature. Online October 21, 2019.