Another year has come and gone. Did we do well this year? Beyond the accumulated likes and comments that float around our feeds for two days before dissipating into data points for social media companies to mine and sell, what makes a good year? The arts have never existed in a vacuum, as external factors politically, socially, economically and beyond play a role in influencing how we connect, no matter where we fall on the spectrum between fine arts and commercial offerings. To reflect on 2025, Men’s Folio interacted with creatives from the Malaysian and Singaporean creative scene to share their thoughts as they wrap up their year and perhaps shed some light on what’s to come.

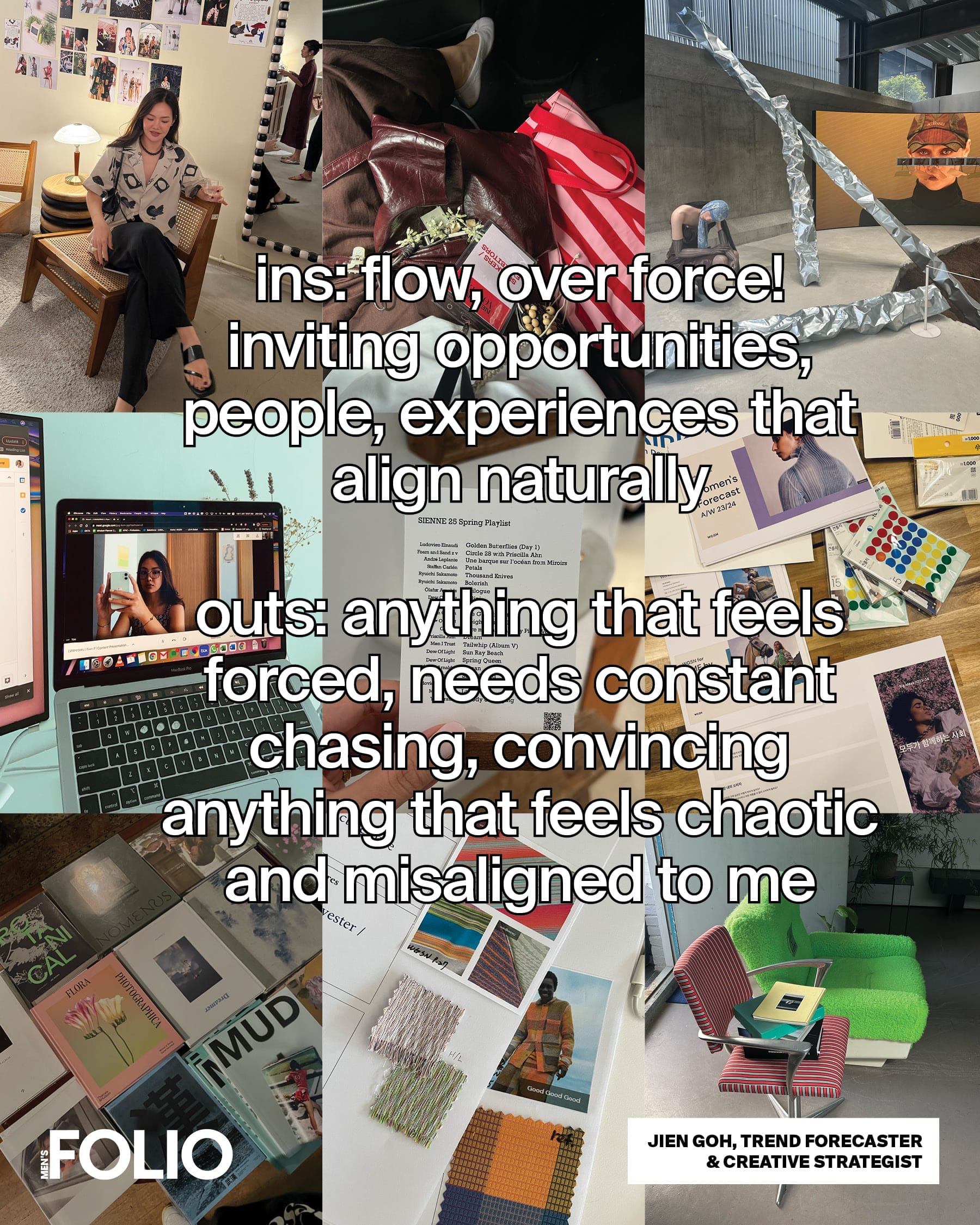

Although the creative scene is often dismissed as non-essential, frivolous and sometimes self-aggrandizing, the greatest shared achievements have been rooted in connecting with others through the language they speak best: art. Malaysian fashion designer and educator Shaofen, who also oversees production for other brands, considered her biggest achievement this year to be her eponymous label’s first runway show in Singapore, along with her role as costume designer and stylist for the Singapore-Malaysia Triennial Cultural Showcase. “Both projects were the first of their kind for me and overlapped in terms of schedules, so managing my time between the two was quite an intense task,” he relates. Having dreamed of exhibiting his work in Paris, figurative artist Israfil Ridhwan was excited to present his first solo exhibition at Art Paris, at the Grand Palais in April. “I didn’t have the luxury of time as I had my reservist the week before and then my third solo performance in Singapore the following week. However, I managed to get through.” Trend forecaster and creative strategist Jien Goh and Faezah Shaharuddin of Studio Kallang found a sense of fulfillment as panelists for Singapore’s Next in Vogue, as they connected beyond their usual audience through their expertise in consumer desire and the future of design.

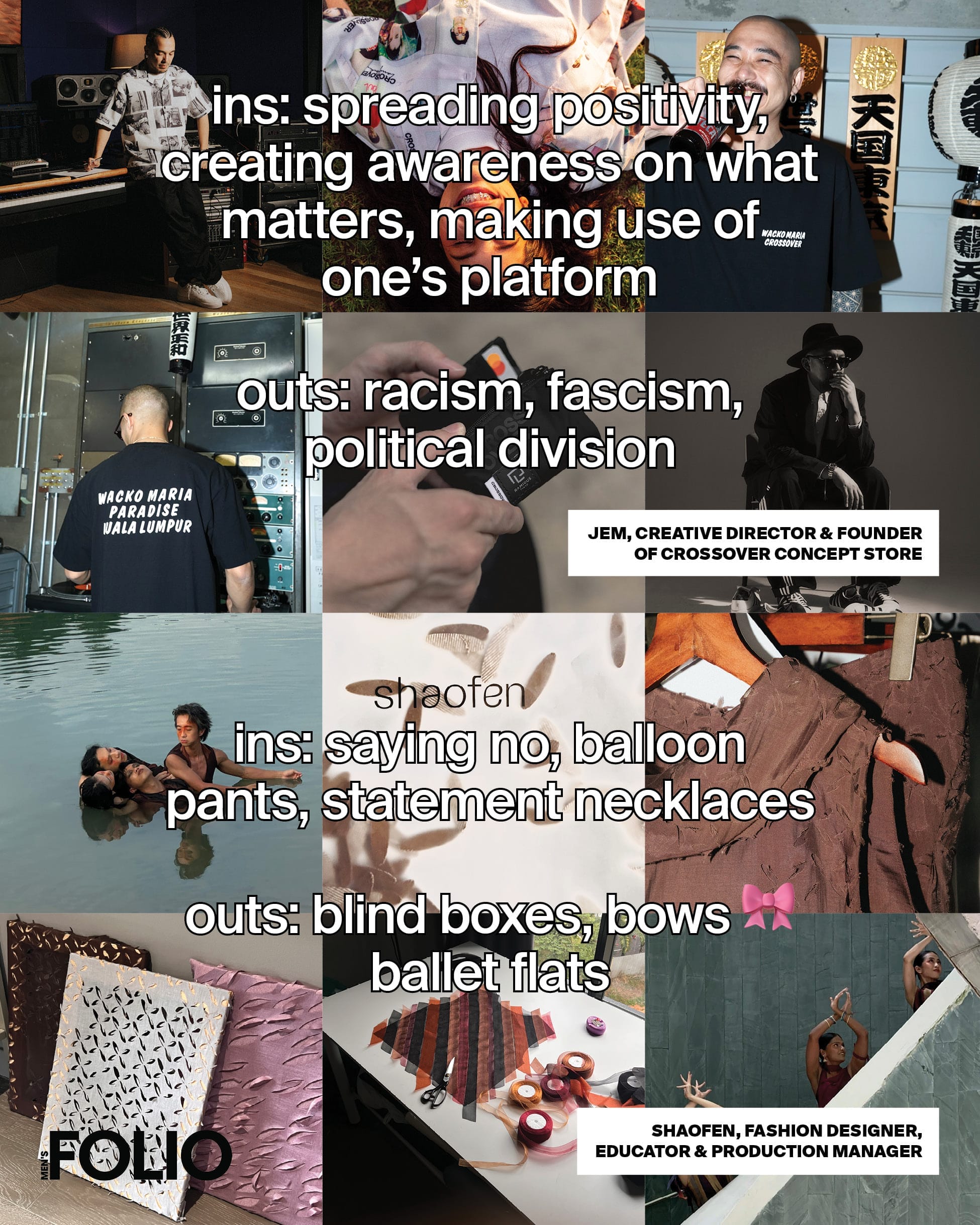

Of course, great feats are not without obstacles, as limitations of time, resources, steep learning curves, and rejection from stakeholders pose challenges in the quest to demonstrate novelty. “Those who know me know that I am not a fan of public speaking. Mental and emotional blocks, which arise from self-doubt and fear of failure, require proactive efforts to overcome. Speaking alongside industry leaders that I admire and respect marked a huge milestone for me,” shares Goh. As passion turned into work for a living, Israfil reminds himself to stay hungry and not become complacent. “The art market has been bad lately and it’s easy to get sidetracked as a freelancer. Sometimes I find myself wondering if everything I do is worth it,” he confesses. Being perceived is part and parcel of being creative; Meeting the demands of the audience without stifling the art itself was an important barrier to overcome. Burger Cham by Mo Sheng Ren, a creative studio that moves between photography, video direction and design, reflects on the “invisible filters” that influence creative production. “Since Malaysia is so diverse, creative decisions have to go through many layers of consideration of the different ways our audience may interpret their work, which in turn reflects on the clients themselves. Many times, we end up going back or adjusting ideas to fit what is considered ‘safe’. That doesn’t make it bad, but it definitely determines how far we can go, while treading the line of being creative and conscious.” Twenty years after founding the select streetwear store Crossover, its founder, Jem, still shares a similar sentiment. “Some of the messages I resonate with and want to express through my designs tend to be too strong, too sensitive and prone to controversy, so there is an element of finding more commercial ways to convey our message without losing meaning,” he shares.

Conservatism or changes in demand shown by customers and consumers tell only part of a larger story. According to Goh, the uncertainties and cost of living crises that plague us as a society have not only led us to buy less but also to be more conscious, purchasing only things that offer experiential and emotional value. This coincides with the phenomenon of “enshittification,” coined by science fiction author, activist and journalist Cory Doctorow, which describes the degradation of digital platforms from user-centric to profit-maximizing and business-centric platforms. The online shopping experience is reduced to an avalanche of flash deals and “buy, buy, buy” requests, and it has made it more difficult for creators to endow their work with meaningful value, especially when the threshold has inflated exponentially. “You’ll notice that lately brands have been pushing for more individual products to be released as a way to preserve their craft,” Shaofen explains. Creating focus is also what Jem seeks at Crossover, as he differentiates himself through community building. “Our consumers are people who religiously follow the brands we market. Beyond the products, they support the ideologies and principles that these labels convey, leading consumer behaviors that transcend prices and the need for fast, disposable fashion,” shares Jem.

At WGSN, Goh and his team discuss the importance of fostering connection, continuity and satisfaction with consumers. “How does a brand move from a relatively transactional mindset to a relational mindset? Can brands facilitate connections within a community of loyal customers, inviting them to become co-creators and stakeholders? How do we move from short-term to long-term relationships in a disposable culture? Can we foster satisfaction through conscious consumption, perhaps adding friction to the purchasing process to curb their desire for excess?”

We constantly feel exhausted because capitalism continually raises the bar for what a feeling of satisfaction should be like, while we experience the increasing costs (emotional, monetary, work-related) of almost everything. Like donkeys trotting after a dangling carrot, we are in a constant search for a new emotional level. With subjects portrayed in often languid states, almost as if the viewer is only glimpsing, without making their own presence known, Israfil and his work recognize the moments of stillness witnessed in solitude: a quiet acceptance of self when no one is there to look or judge. Longing for more, but constantly facing the risk of being perceived negatively, the idea was never to deny community in search of total acceptance, but perhaps to point to a form of kinship as we navigate a community. As the father of a young family, Cham is still trying to find his balance. “I start working after my family goes to bed so I can concentrate. My wife calls me ‘afternoon dad’ since that’s when I wake up. It’s not the perfect system, but it’s a routine that works for us right now.”

Given the nature of the industry, can what they do be considered simply a job, or does it require more than just hard skills and a sense of responsibility to create something that matters? “There are jobs that pay the bills, and then there are projects where I can express something: an idea, a feeling, or a point of view,” Cham shares. Although not all projects have to be deep or meaningful, you always find gratitude in those that allow you to express yourself. While Jem has had the opportunity to learn and connect with cultures beyond her own, Faezah has been able to find meaning from her own cultural environment and community. “It’s a tough industry, and I think it’s even tougher when you can’t find meaning in the work.” Shaofen’s interest in the arts and fashion may have grown into her career, but it took her years of work before she achieved some stability in it. “All of that worked because I found purpose in each project by identifying the goal I wanted to achieve,” adds Shaofen. Driven by passion and the ability to create on your own terms is “the greatest luxury you can have as a creative and brand owner,” he says – most stay because it’s what they do best. “When I started art school, I didn’t have a plan B. The only plan was and is to be an artist and make a living from it,” Israfil shares. For Faezah, her work is a tool of introspection and resonance; for Goh, it’s his way of connecting the dots between the past, present and future.

As artificial intelligence becomes more capable of replicating human skills, it sees a real opportunity for brands to truly differentiate themselves by leveraging their artisanal heritage through genuine craftsmanship. To counter the state of boredom that currently afflicts us, we can expect an emergence of rational optimism, a belief that recognizes the possibility of positive change, while considering challenges and setbacks. “In other words, optimism is a logical, evidence-based response to negativity,” he shares. While many might see the industry as a bubble that feels removed from reality, given how tied it is to our own humanity, perhaps it could be more of a crystal ball that prophecies where we are supposed to be in the future, or in due course. Maybe.

Once you’re done with this story, click here to catch up on our December/January 2026 issue.

The post Despite Everything: 2025, in Reflection appeared first on Men’s Folio.