NIBIB-funded scientists have created a novel 3D brain tissue system that better mimics the tumor environment in patients than previous systems. Made with extracellular matrix (ECM) from pig brains and seeded with brain tumor cells from patients, the system is revealing tumor/ECM interactions that aid tumor progression, which may enable new treatment avenues. The study also provides a vital clue about how adult brain tumors become resistant to drug treatment over time.

Two common types of brain tumors remain particularly deadly: ependymomas in children and glioblastomas in adults. Both have a median survival of only 1 to 2 years after diagnosis.

A research team led by David L. Kaplan, Ph.D., distinguished professor and director of the Center for Tissue Research and Engineering at Tufts School of Engineering, developed the new model. A good model of the tissue-engineered brain ECM microenvironment is important because, beyond physically supporting and connecting neuronal tissues, the ECM also helps guide cell growth and development.

“One of the reasons tumors thrive is that they adapt to growing in the surrounding matrix of proteins and other molecules known as ECM,” explains Seila Selimovic, Ph.D., director of the NIBIB program in Engineered Tissues. “Kaplan and his colleagues have made a significant leap in being able to study the specific mechanisms used by the tumor to alter the surrounding ECM in a way that supports tumor growth. With this they can now also examine possible mechanisms that result in tumor resistance to chemotherapy.”

“The first step was to precisely mimic in our tissue culture system what happens in the patient,” explains Kaplan. “Once this is done, we can add and subtract various components to our culture and obtain new information, such as which components make tumors grow faster and which act to inhibit that growth.”

Kaplan drew on his extensive experience using silk to create implantable devices, such as surgical screws and porous scaffolds that support the growth of new cartilage. The tissues do not recognize the silk as foreign, so no inflammation or other immune response occurs.

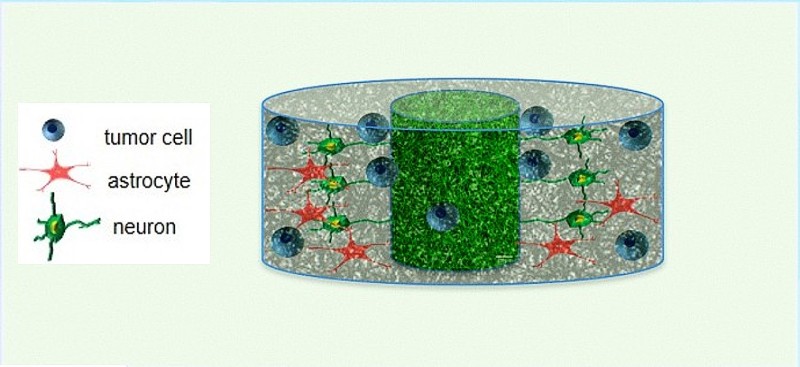

The team started with a 3D block of porous silk and then seeded it with matrix material from fetal pigs to support the childhood tumors and material from adult pigs to support the adult tumors. This biocompatible silk framework served to support the transplanted ECM, additional factors necessary to support human tumor cells such as hyaluronic acid and collagen, as well as additional tumor cells, without affecting the natural cell/ECM interaction.

“The system came up with some fascinating results,” Kaplan said. “For example, we found that fetal ECM tissue supported more robust tumor growth than adult ECM.” He explained that this phenomenon was intriguing given previous reports that more rapidly proliferating tumors have the ability to alter adult ECM so that it becomes similar to fetal ECM. According to Kaplan, these results suggest that inhibiting a tumor’s ability to alter the ECM toward a more fetal phenotype could be a target for potential therapies.

An unexpected observation was the formation of extracellular fat droplets released by adult tumor cells, something that had never before been observed in less sophisticated culture systems. The working hypothesis put forward by the research team was that the drops can capture drugs used to treat glioblastoma in adults before they can reach the tumor cells. This would be consistent with what is found in the clinic: the tendency of adult brain tumors to become resistant to drug treatment over time.

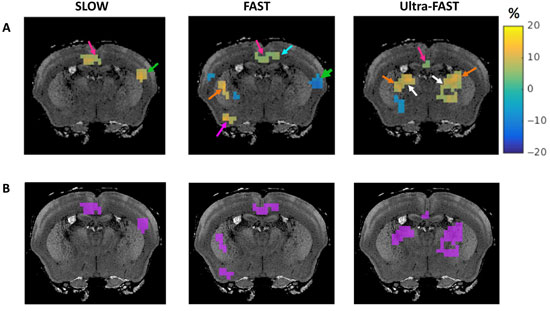

The studies were aided by an imaging system called two-photon microscopy, which provided non-invasive monitoring of what was happening in the cultures in real time through the laboratory of Irene Georgakoudi, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Tufts University.

Based on initial results, the team is excited about using the system to rapidly test drug candidates that have tumor-inhibiting activity. In the future, the system could be used to identify the most effective treatments by testing potential drugs against 3D ECM cultures that are specific to each patient.

The results were published in the October issue of Nature Communications.1. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Tissue Engineering Resource Center P41 grant (EB002520) from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke, an NIH Research Infrastructure grant, and grants from NSF and USDA.